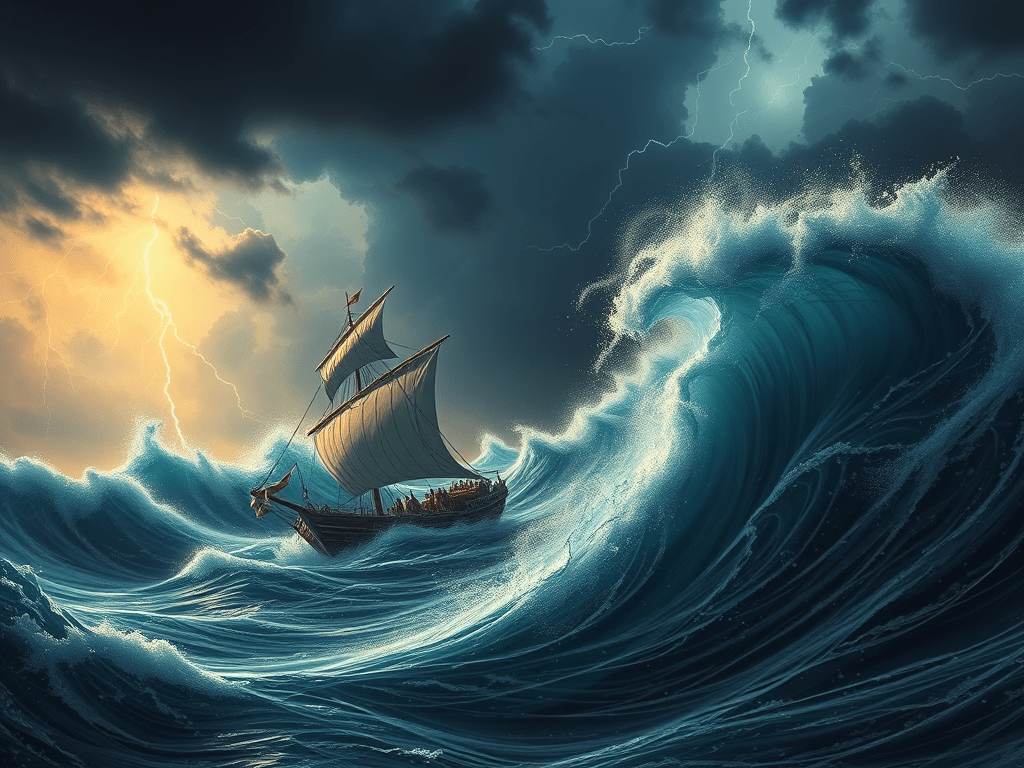

But the Lord hurled a great wind upon the sea, and there was a mighty tempest on the sea, so that the ship threatened to break up (Jon. 1:4).

Jonah 1:4 illustrates God’s sovereignty and power through His forceful intervention, as seen in the Hebrew verb tul (טוּל), meaning “hurled,” which conveys deliberate and forceful action. The “great wind” (ruach gadol) and “tempest” (sa’ar) reflect the overwhelming chaos God uses to disrupt Jonah’s flight. It’s clear that Jonah is causing his own chaos by disobeying the King of the natural world. Furthermore, when we attempt to run from God, He will create a way to get our attention so that we repent and seek refuge in His divine will.

The personification of the ship, “threatening to break up” (chishevah le-hishaver) intensifies the drama, emphasizing the storm’s divine origin. The word “threatened” (tira’ash) comes from the root ר-ע-ש (resh-ayin-shin), which means “to shake,” “to quake,” or “to tremble.” It indicates an intense shaking or violent movement. This isn’t merely a rough sea; it is an overwhelming storm that causes the ship to violently sway or shudder, as if it might split due to the strength of the waves and winds.

In the ancient Near East, the sea symbolized chaos and divine power, making this storm a clear sign of God’s displeasure and pursuit of Jonah. The mythological texts of the ancient Near East, such as the Enuma Elish, Ugaritic epics, and Egyptian cosmology, depict gods who struggle to establish order by battling chaotic forces like Tiamat, Yam, or Apophis. These myths portray deities as limited beings, engaging in conflict to assert their power and often reliant on victory to maintain order.

In stark contrast, the God of Jonah is not depicted as one among many or as a deity in conflict with chaos but as the supreme and sovereign Creator who effortlessly commands all of creation, including the chaotic sea (Jon. 1:4). Unlike the gods of mythology, who often reflect human frailty and limitations, the God of Jonah demonstrates complete authority, hurling the storm with precision and purpose to accomplish His divine plan.

This portrayal underscores the monotheistic conviction that the God of Israel is not bound by or in contest with chaos but is its ultimate master, using it as a tool to reveal His will and direct His prophet. Also, when Jonah mentions that He serves the God who created the land and the sea, this “God” is not confined to a specific area. The Lord of the Hebrews is not a territorial god like many of the false gods that were worshipped in the Ancient Near East. It’s a paradigm shift that Jonah said he worships the God who made both the sea and land, encompassing all of creation.

This moment parallels other biblical accounts of God’s authority over nature, such as the parting of the Red Sea (Exod. 14:21-22), the sailors’ cry for deliverance in Psalm 107:25-30, and Jesus calming the storm in Matthew 8:23-27, where nature again submits to divine will. As you recall, when Jesus calms the storm, they proclaim: “What kind of man is this? Even the winds and the waves obey him!”

Moreover, Peter said that he was a sinful man when he witnessed Jesus calm the storm because his faith was weak. He should have felt secure in the boat with the God who created everything, but of course, we all struggle with this in our everyday lives. We should never really fear anything in life when we know the one who created life. While Jonah was being disobedient, unlike Peter, Jonah knew that the Lord was in complete control of this situation and that the raging sea was a direct result of his disobedience.

Moreover, the storm contrasts nature’s obedience with Jonah’s disobedience, reinforcing that no one can escape God’s purpose. This verse serves as a reminder that challenges in life—whether through work stress, personal struggles, or external crises—can act as divine interventions to redirect us toward God’s will and deeper dependence on Him.

Then the mariners were afraid, and each cried out to his god. And they hurled the cargo that was in the ship into the sea to lighten it for them. But Jonah had gone down into the inner part of the ship and had lain down and was fast asleep (Jon. 1:5).

Jonah 1:5 offers significant grammatical and syntactical insights. The phrase “All the sailors were afraid” (וַיִּירְאוּ הַמַּאֲרוֹת) uses the verb “were afraid” (וַיִּירְאוּ, vayyiru) in the waw-consecutive imperfect tense, which is commonly used in Hebrew narrative to denote consecutive actions. This tense indicates that the sailors’ fear is not a single moment of distress, but a continuous, escalating reaction to the storm.

Furthermore, it says the mariners hurled the cargo that was in the ship. The act of throwing the cargo overboard is a desperate, immediate response to the storm. The phrase “they threw the cargo into the sea to lighten the ship” (וַיַּשְׁלִיכוּ אֶת-הַמַּטְּעָה הַיָּם, vayashliku et-hamatt’ah hayam) uses the verb “threw” (yashliku), which comes from the root ש-ל-ך (shin-lamed-khaf), meaning “to cast” or “to hurl.”

This choice of verb suggests a violent, forceful action, emphasizing the urgency of the situation. The sailors are not merely tossing cargo off the ship in a calculated manner but are throwing it with the intent to save their lives. The cargo represents the wealth or livelihood that the sailors have on board, which they are willing to lose in exchange for their survival.

The mariners were aware, even as they worshipped other gods, that this God was more powerful than the ones they served. It’s ironic that they had a propensity to bow down and give allegiance to this Hebrew God, and yet Jonah is complacent towards Yahweh because he is “familiar” with God. But make no mistake, Jonah should be afraid and have the same reaction as the mariners do in this situation, but his heart seems to be hardened.

Jonah’s sleep serves as a metaphor for spiritual complacency. In the Bible, sleep is used as a metaphor for being spiritually “asleep” or unaware, as seen in passages like Matthew 25:5, where the foolish virgins fall asleep before the arrival of the bridegroom. Jonah’s sleep can be viewed in this way—his refusal to acknowledge the storm, the seriousness of his rebellion, and the divine purpose behind it demonstrates a lack of spiritual alertness.

As Christians, we should never be complacent towards God. When the world goes through turmoil, there are unbelievers who even cry out to a higher power to find an answer to the conflict or serious situation they may be in. For example, when a huge tsunami hit Indonesia back in 2004 and killed several thousand people, there were many who prayed and asked the Lord to rescue them from the grave, terrible situation.

So the captain came and said to him, “What do you mean, you sleeper? Arise, call out to your god! Perhaps the god will give a thought to us, that we may not perish” (Jon. 1:6).

The grammatical structure of the captain’s speech is straightforward, with an imperative command sequence: “What are you doing asleep?” (Mah-lach ta’arosh?), “Get up!” (Qum!), and “Call on your god!” (Qara el-elokecha!). The use of imperatives here conveys a sense of urgency and frustration. The captain is demanding immediate action, understanding the perilous nature of the situation.

The phrase “What are you doing asleep?” (מַה-לָּךְ, mah-lach) employs a rhetorical question, which emphasizes the absurdity of Jonah’s behavior. Jonah, the prophet of God, who should be leading the charge in calling on divine intervention, is instead passively sleeping below deck, indifferent to the lives at stake. Moreover, this idea of calling on your gods is a pagan concept because multiple gods would be invoked to hope for a solution. Even though the captain has no knowledge of the one true God, He is behaving correctly in fearing his life and calling for a powerful force to save them.

There are several passages that mirror this complacency within true worshipper of God. For example, the church in Sardis (Rev. 3:2-3) and Paul’s admonishment to the church in Ephesus (Eph. 5:14) warn believers to wake up from their spiritual slumber so they don’t get caught off guard. In Luke 22, Jesus rebukes his disciples for falling asleep instead of praying shortly before the Lord is handed over to the Romans to be arrested and crucified. It’s therefore essential as Christians today to learn from all the stories from the Bible that teach us to be vigilant and alert, for our enemy the devil is roaring like a lion, seeking whom to devour. So be alert and sober-minded!

And they said to one another, “Come, let us cast lots, that we may know on whose account this evil has come upon us.” So they cast lots, and the lot fell on Jonah (Jon. 1:7).

The sailors, desperate to understand the cause of the storm, decide to cast lots, a method of divination common in the ancient world to discern the will of the gods. The phrase “Come, let us cast lots” (לְכוּ וְנַפִּילָה, lekhu v’naphilah) uses the imperative verb lekhu (“come, let us go”) and naphilah (“we will cast”), reflecting an urgent collective action.

The syntax here emphasizes their immediate response to the storm, seeking a divine answer. Casting lots was a common practice in the ancient world, including among the Israelites. For example, in Leviticus 16:8, lots were cast to determine which of two goats would be sacrificed on the Day of Atonement, showing the significance of lots in religious decisions.

Similarly, in Joshua 7:14-18, lots were used to identify Achan as the one who sinned, demonstrating how casting lots served as a method for divine judgment. In Jonah 1:7, the sailors’ casting of lots reveals their belief that the storm is not simply a natural occurrence but a divine judgment.

Furthermore, the outcome of the lot falling on Jonah underscores God’s control over the situation, aligning with His will. This practice is echoed in the New Testament, as seen in Matthew 27:35 when soldiers cast lots for Jesus’ clothes during the crucifixion, reinforcing the idea of lots as a means of determining fate in significant, often judgment-filled moments.

The fact that the lot fell on Jonah shows God’s sovereignty. It wasn’t a random chance that Jonah was chosen among all the people on the ship–he was directly responsible for the precarious situation and everyone knew it. This illustrates how we can’t run from the divine judgment of God. Sooner or later, your sin will find you out (Num. 32:23). While we may still receive the consequences for our sins, thankfully God will invoke forgiveness and seek a way for us to be reconciled and restored.

Subscribe to get access

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

and since christians can’t even agree on what their god considers a “sin”, your impotent threats are meaningless.

LikeLike

I appreciate your opinions and wish you the best. Happy New Year to you.

LikeLike